What Motorcycle Engines Teach Us About Engineering Trade-offs

If you spend enough time reading about motorcycles, engines, or performance numbers, you start noticing a strange pattern. Two bikes can make almost the same horsepower on paper, have similar weight, and even target the same buyer, yet feel completely different once you ride them. One feels calm, planted, and effortless. The other feels manic, buzzy, and always asking to be pushed harder.

That difference is not magic. It is the engineering trade-offs that were made.

Motorcycle engines are one of the cleanest real world examples of trade-offs in engineering. There is no hiding behind abstractions. You change one thing, and something else immediately moves. You gain torque, you lose revs. You gain smoothness, you lose simplicity. You gain reliability at high RPM, you lose character down low.

If you work in software, especially backend or systems engineering, this should feel very familiar. The shapes are different, but the decisions are the same.

Let us break this down by looking at bore and stroke, cylinder count, power delivery, and then draw a straight analogy from engines to software systems.

Bore, Stroke, and the Shape of Power

At the heart of every engine is a simple geometric decision. How wide is the cylinder bore and how long is the stroke.

A long stroke engine has a piston that travels a longer distance up and down. A short stroke engine does the opposite, it is a wider cylinder that moves less distance up and down, and by that logic it moves faster.

Long stroke engines tend to make torque earlier because the leverage is better. Think about pushing a door right near its hinge on one end and then pushing it at the opposite end. The distance from the hinge is larger in the latter case and you can open or close the door with little to no effort.

Effortless-ness is the prime characteristic of torque, this means the bike feels strong at low RPM. You open the throttle and it moves without needing to be screamed. Which means these engines are great for pulling and carrying stuff too. Imagine a truck carrying loads of material (maybe uphill too), there is no way its engine would be engineered to rev out high.

And one of the best examples when it comes to motorcycles is our very own Royal Enfield and their famous long stroke engines, like the current J series which I happen to own. There is a reason these motorcycles have an image of projecting machismo and power, the engine character suits it perfectly.

Short stroke engines are happier spinning fast. The piston travels less distance per revolution, so stresses at high RPM are lower. This allows higher redlines and more power up top. The trade-off is that low end torque usually suffers. Every sports and race type motorcycle you will see, especially made for racing at tracks would have this engine configuration. That’s why these engines and their sounds are associated with a racer image. For more technical details on engine geometry, check out this explanation of bore and stroke.

Neither is better in isolation. They are optimized for different use cases.

To me a good analogy for this is something like batch processing vs stream processing in software.

Batch-oriented systems do a lot of work in one go. You collect data, aggregate it, transform it, and produce a meaningful result in a single run. Each batch execution is expensive, but the value you get from it is high. You do not need to run it constantly for it to feel productive.

These systems feel powerful. You trigger a job and something substantial happens. But if you try to run batches continuously at high frequency, the system starts to strain. Resource contention increases, latency becomes unpredictable, and failure impact grows.

That is a long stroke philosophy.

Stream-oriented systems do very little work per event. Each message or record is handled quickly and cheaply. The assumption is not that one event matters much, but that the system will see a lot of them. Performance comes from being able to repeat this small unit of work safely and consistently at scale.

These systems feel underwhelming if you look at any single event in isolation. Nothing dramatic happens. The power only becomes visible when the stream is flowing. But when used correctly, they scale far beyond what batch systems can handle.

That is a short stroke philosophy.

The key insight is that both approaches can reach similar overall throughput, just like two engines can make similar peak horsepower. The difference is how they get there and how they feel to operate.

Batch systems, like long stroke engines, are forgiving. You can interact with them casually and still get value. Stream systems, like short stroke engines, assume discipline. They assume you will keep them in their optimal operating range.

Problems arise when expectations and design philosophy do not match.

If you design a system around streaming but users expect batch-like outcomes per interaction, the system feels weak and frustrating. If you design heavy batch jobs but usage demands constant execution, the system feels brittle and unreliable.

Cylinder Count and Parallelism

Cylinder count is one of the most obvious differences between engines. Single cylinder, parallel twin, V twin, inline three, inline four.

Each step up adds complexity. More moving parts. More friction. More cost. But also more smoothness and more potential power.

A single cylinder engine is brutally honest. One big piston doing all the work. Strong pulses. Lots of vibration. Simple, light, easy to maintain. It gives you torque early and runs out of breath quickly. Examples include classic Honda CRF dirt bikes and KTM EXC enduro motorcycles.

An inline four is the opposite. Multiple smaller pistons sharing the workload. The power delivery is smooth, almost electric. It can rev high and make serious top end power. But it is heavier, more complex, and often feels weaker at low RPM unless engineered aggressively. Think of Yamaha R1 or Honda CBR1000RR sportbikes.

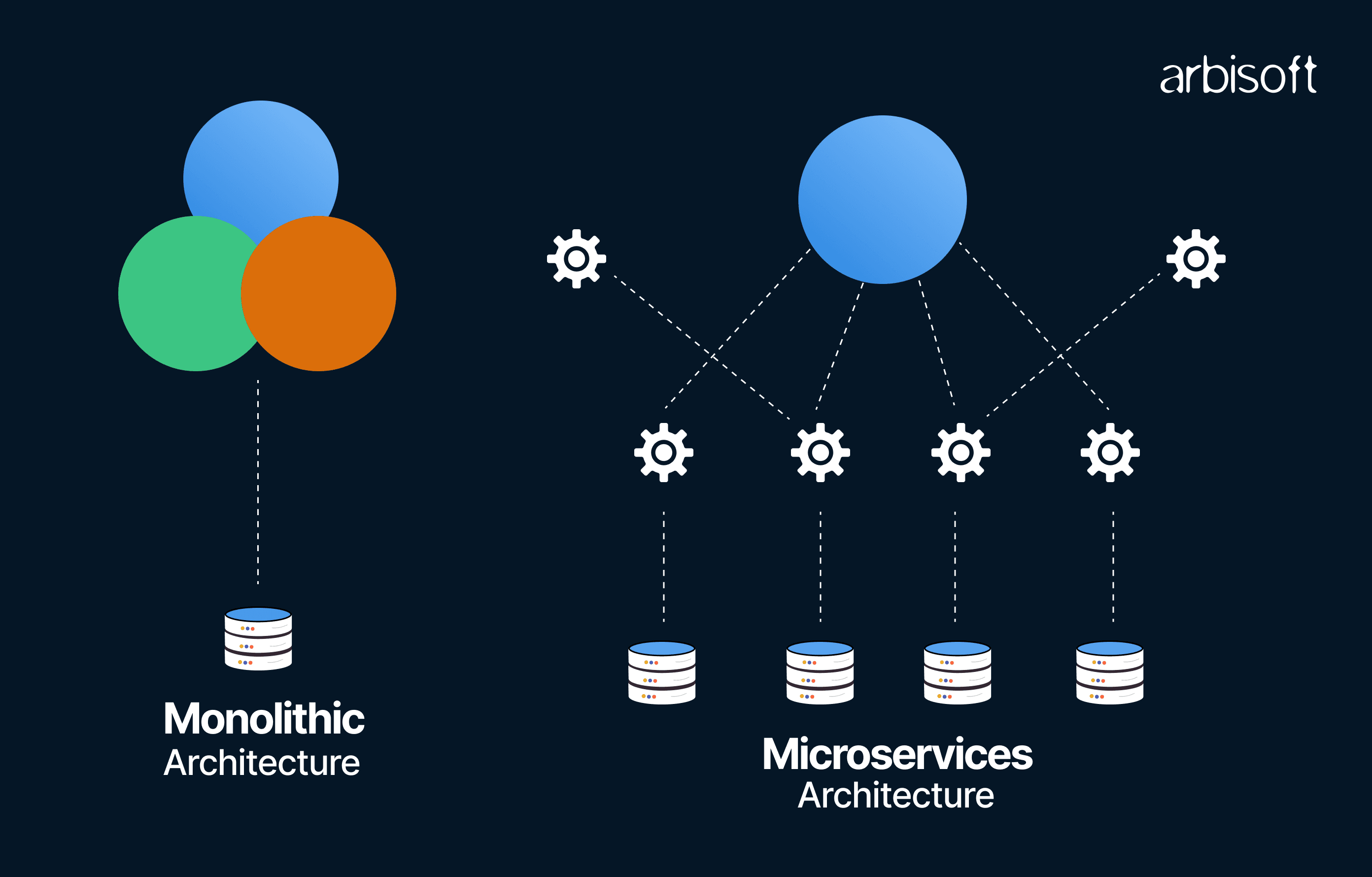

A single cylinder engine is a monolith.

Everything happens in one place. One piston does intake, compression, combustion, exhaust. The entire system is easy to understand because all the logic is centralized. When something goes wrong, you usually know where to look. Maintenance is straightforward. The trade-off is obvious. There is a hard ceiling on performance. You can only push one piston so far before vibration, heat, and mechanical stress become unacceptable.

Monolithic software systems behave the same way. All business logic lives together. State is local. Debugging is easier because the execution path is visible. Deployments are simpler. But as load grows or requirements expand, you start hitting limits. Scaling often means scaling everything, even the parts that do not need it. For a deeper dive into monolithic vs microservices architecture, Martin Fowler’s article is an excellent resource.

Now move to a twin cylinder engine.

You have split the workload. Each cylinder does less work per cycle, but together they produce more usable output. The engine is smoother. Power delivery is more balanced. At the same time, you introduce coordination problems. Firing order matters. Balancing matters. Packaging becomes harder.

This is the early step into modular systems. Still tightly coupled, but already benefiting from separation of responsibility.

An inline four is microservices territory.

Now the workload is distributed across multiple smaller units. Each piston is optimized for a specific role in the system. The engine can rev higher, make more power, and feel incredibly smooth because no single component is overstressed. But this comes at a cost. The engine is wider, heavier, more complex, and far more sensitive to poor tuning.

Microservices follow the same pattern. Each service does less work individually, but the system as a whole can scale massively. You gain flexibility, independent deployments, and fault isolation. But you now pay for coordination. Network latency replaces function calls. Debugging crosses service boundaries. Observability becomes mandatory, not optional.

The important insight is that adding cylinders does not just add power. It fundamentally changes how the system behaves.

A single cylinder engine has character because everything happens in one place. You feel each combustion event. A monolith feels the same way. Predictable, opinionated, and sometimes rough, but deeply understandable.

An inline four feels refined and effortless, but also distant. You get performance without drama. A microservices system feels similar. Powerful, scalable, but harder to emotionally grasp because the behavior emerges from interactions rather than a single flow.

Neither approach is superior by default.

Motorcycle engineers do not put inline four engines into dirt bikes meant for tight trails. Software engineers should not put microservices into products that are still finding their shape.

The mistake in both fields is treating complexity as progress.

Cylinder count is not about making more power. It is about choosing how that power is produced, coordinated, and felt. Architecture works the same way. You are not just scaling performance. You are choosing where complexity lives and who has to deal with it.

Cooling, Reliability, and Long Term Thinking

Another subtle trade-off in engines is cooling and longevity.

Air cooled engines are simple. Fewer parts. Less weight. Easier maintenance. But they have tighter limits on performance and thermal consistency.

Liquid cooled engines can push harder. Tighter tolerances. Higher compression. More power. But more complexity and more failure points.

This is not unlike choosing between simple architectures and highly optimized ones.

A monolith with clear boundaries is like an air cooled engine. It may not scale infinitely, but it is robust and understandable. A microservices architecture is like liquid cooling. Powerful, flexible, and efficient at scale, but requiring discipline, tooling, and operational maturity.

Neither choice is wrong. The mistake is mismatching the solution to the problem.

Motorcycle engineers do not put race level cooling systems on commuter bikes unless necessary. Software engineers often do the equivalent by adopting complex architectures far too early (a mistake us engineers make way too often).

Riding Style and User Behavior

Perhaps the most important lesson motorcycles teach is that users matter.

An engine is not just designed in isolation. It is designed for how people will use it.

Commuters want smooth torque and reliability. Track riders want top end power and sharp response. Tourers want relaxed cruising and low fatigue.

Engineers tune for this reality.

In software, we often design for how we wish users behaved, not how they actually behave.

We assume ideal request patterns. Perfect input. Rational usage. Then reality hits, and the system struggles.

Motorcycle engineering accepts messiness upfront. Software engineering often resists it until production incidents force the issue.

Final Thoughts

Motorcycles are honest machines. You feel the trade-offs directly in your hands, feet, and spine. There is no abstraction layer to hide behind.

If more software engineers thought like engine designers, fewer systems would chase theoretical perfection and more would deliver real world excellence.

In both domains, the goal is the same. Build something that works well where it actually lives, not where the spec sheet says it should.

And sometimes, the imperfect solution is the most human one.

Well, this was it for this one. It was a very different kind of post that may not even be relevant, but I could not help but draw comparisons as I saw them in my day to day life. Until next time!

— Ray

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: